On Monday, December 14, 2020, the Spokane City Council voted unanomously to change the name of “Fort George Wright Drive” to “Whistalks Way.”

This action begins to correct a series of significant wrongs spanning 162 years aimed at the native population in our area .

U.S. Army Col. George Wright was responsible for, among other things, the execution of Yakima sub-chief Qualchan, along with more than a dozen other local natives in 1858.

The name of the one-mile stretch of 4-lane road will honor Qualchan’s wife Whist-alks, who was known as a warrior woman that fought to save her husband from being hanged.

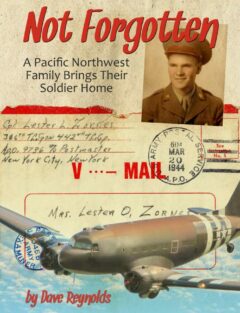

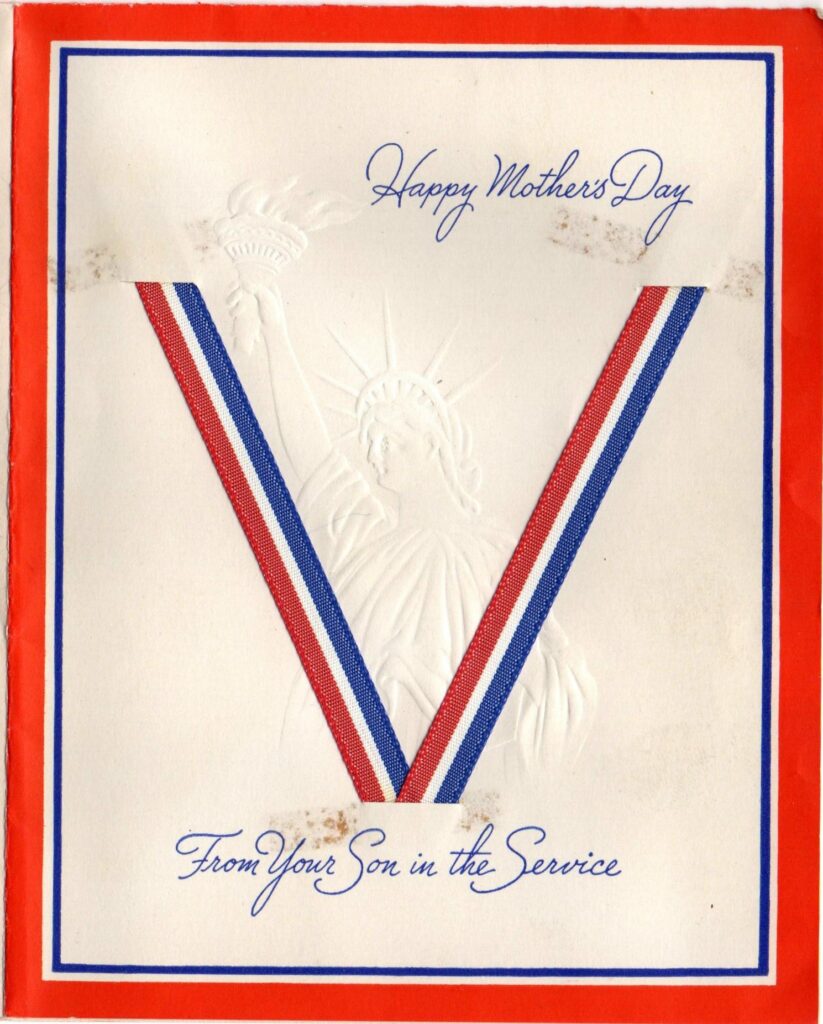

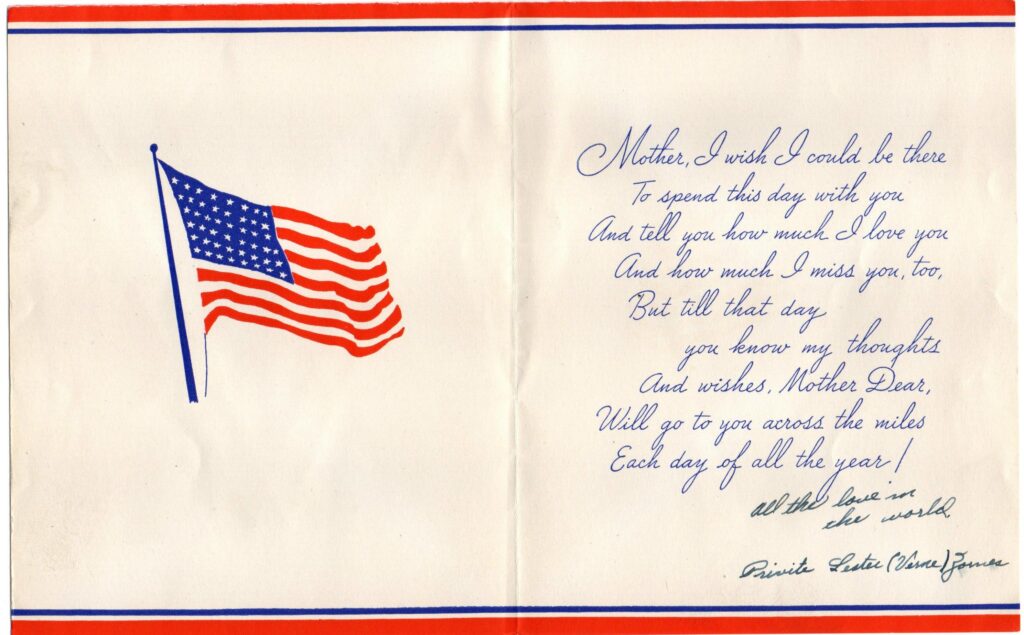

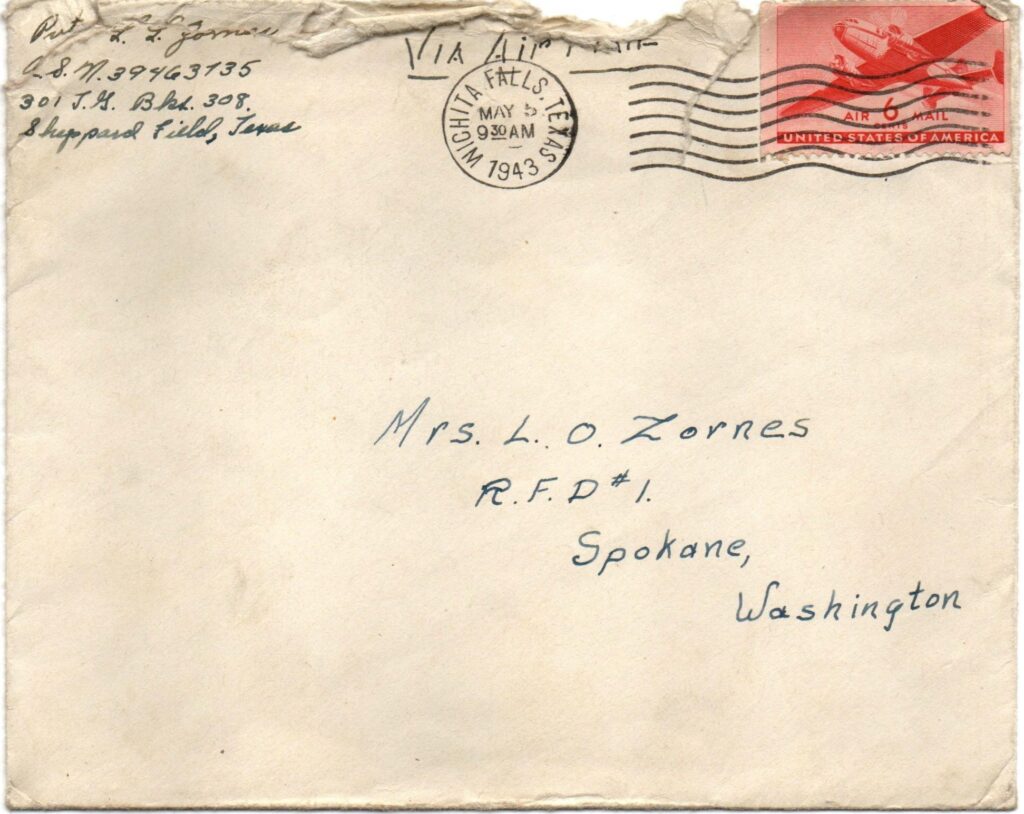

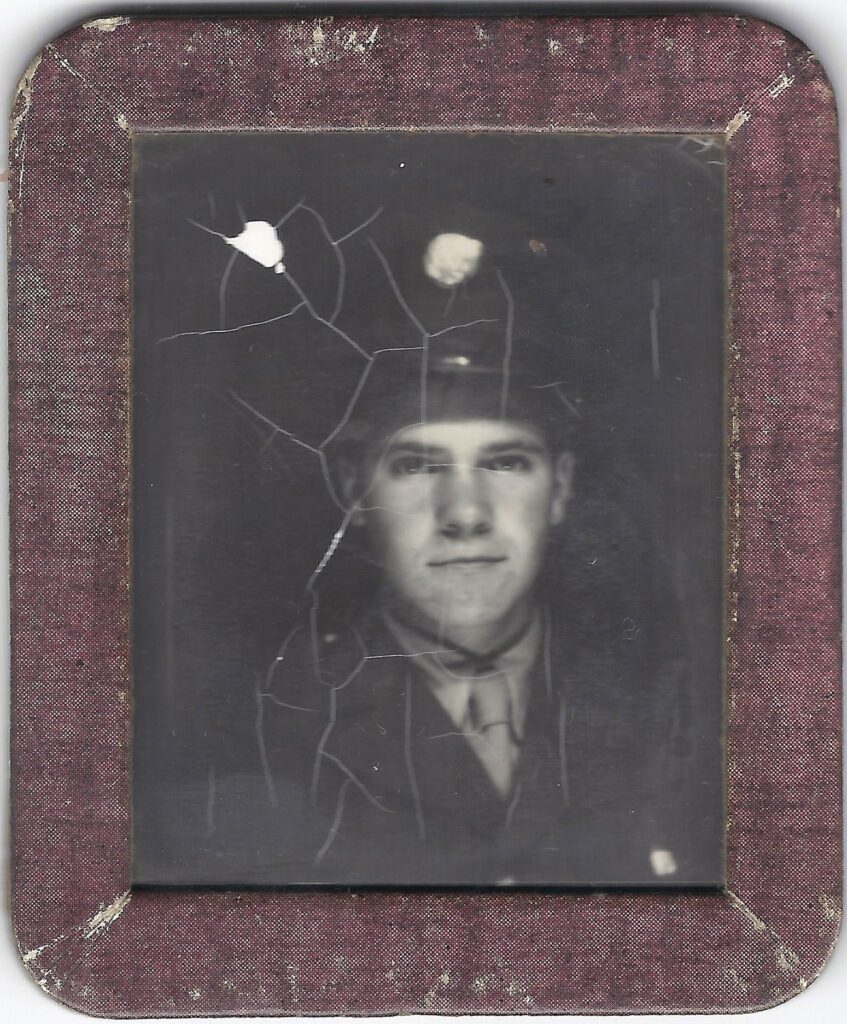

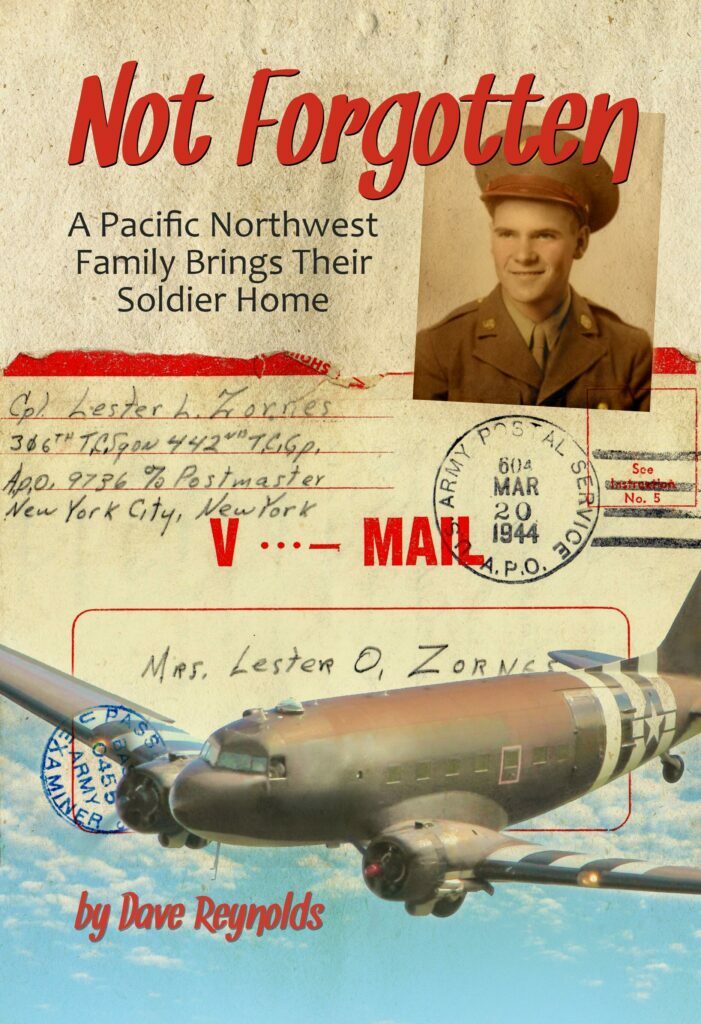

Here is an excerpt from Chapter 13 of “Not Forgotten: A Pacific Northwest Family Brings Their Soldier Home,” in which I describe the incident that led to the naming of “Hangman Creek,” also known as “Latah Creek,” along which my mother’s family settled in the 1930s and 1940s :

When [my mother’s brother] Verne was about ten years old [about 1935], the family moved to a farmhouse they rented about three miles south of Spokane, near a quiet neighborhood locals dubbed “Vinegar Flats.” This valley was home to the Keller-Lorenz Vinegar Works, a particularly fragrant factory that took advantage of the area’s plentiful apple orchards to make cider, malt, and white wine vinegar. Even though the factory closed in the late 1950s, and the canyon no longer smells like pickles, the neighborhood’s nickname lingers.

By the time Verne was 15, Grandma and Grandpa had purchased land a few hundred feet away from their rental on the bank of what is called “Latah Creek” on some maps. If you ask any local old timers where Latah Creek is, however, you’re just as likely to get a blank stare as a reliable answer. Or you might get directions to Latah, a tiny village with that name 30 miles southeast of Spokane Valley.

Ask about “Hangman Creek,” and we’ll give you precise guidance that would turn any GPS green with envy.

I was afraid of Hangman Creek – with good reason. I was an odd child, but I was no dummy. I had read that children’s horror story “Three Billy Goats Gruff” enough times to know evil can wait for long stretches of time in dark, chilly places under bridges. Because this creek had the word “Hangman” in its name, I understood monstrously patient masked creatures (I pictured dozens of drippy Shrek look-alikes with black ski-masks and no sense of humor) could hide like trolls under every bridge, with the sole purpose of snatching up little boys and girls to string up and nibble on.

As an adult, I learned about the truly gruesome series of events that gave the creek its creepy nickname. These took place during the lead-up to the Civil War, as the stream of white settlers from the East and Mid-West kept filling up what in the 1850s was Oregon Territory. Several local Native American tribes started raising a ruckus at what seemed like an unending invasion of their ancestral homelands, which, of course, it was.

In May of 1858, the U.S. Army dispatched Colonel Edward Steptoe to travel north from Ft. Walla Walla to meet with local tribal leaders in Colville and persuade them to calm down. But some of the tribes were done playing nice. They confronted the troops near Rosalia, about 30 miles south of Spokane. Because Steptoe wasn’t expecting any problems, his 150 or so soldiers carried very little ammunition. Under the cover of darkness, they made a skillful tactical retreat through the Palouse back to Walla Walla.

Four months later, Colonel George Wright decided to put a decisive end to all these “troubles.” To cripple the economic vitality of the local Indians, Wright ordered the slaughter of hundreds of prized horses near what is now State Line, Idaho. This got everyone’s attention. Wright then called for leaders from several tribes to gather and sign a treaty at a shallow crossing of the creek, some 25 miles upstream from where Spokane would later sprout up.

One of those leaders was Chief Qualchan of the Yakima tribe. He rode proudly into camp, apparently expecting to negotiate a deal with the Army.

Wright had something else in mind. He promptly ordered his soldiers to hang Qualchan from a tree along the bank of the creek. Before Wright was finished, more than a dozen Yakimas were executed in much the same way.

A stone marker at the site commemorates the hangings. It also notes that just a few hundred feet away, the tribal leaders who were not strung up signed a peace treaty, pretty much putting the kibosh on any organized resistance.

The name “Hangman Creek” stuck almost immediately.

Maps published by the U.S. Geological survey still recognize the name “Hangman Creek.” Toward the end of the 20th century, Spokane County and the State of Washington officially opted for the earlier “Latah Creek,” perhaps as a conciliatory nod to the tribes, or to keep from scaring away tourists and nervous little boys and girls.

In an act of in-your-face arrogance, the military in 1899 established Fort George Wright about a mile and a half north of where Hangman Creek empties into the Spokane River. For a time during World War II, Fort Wright became Pacific Northwest Headquarters for the U.S. Second Air Force. It provided ground school training for pilots and even top-secret training for spies.

In an act of poetic irony, the facility in 1990 became home to the Mukagawa Fort Wright Institute, an American language Japanese student exchange school.

I’ve also learned the pretty little creek (or “crick” as many pronounce it) forms from melted winter snow pack from the western-most slopes of the Rocky Mountains. It flows about 100 miles in a generally north and west direction, with dozens of tributaries draining water from nearly 700 square miles of the Palouse. Frequently in the early spring, higher than usual levels of snow melt can force the creek to surge over the edges of its banks.

The creek’s volume is highest through the Vinegar Flats canyon immediately before it joins the Spokane River west of downtown Spokane. The walls of the canyon give it the shape of a long spade, with the tip pointed generally toward the northwest. The mostly flat floor of the canyon narrows to about 300 yards.

Three features dominate the canyon floor, each meandering from the southeast towards the northwest: the creek, the Burlington Northern Railroad, and State Route 195, known locally as the Pullman Highway. From a bird’s point of view these three ribbons appear pinched together at a narrow spot centered on the bottom of the canyon.

That narrow spot is where the Zornes family purchased eight acres to put down roots in 1940. The long rectangular property was scrunched between the creek on the east and north, and a 25-foot high pile of rock that made up the rail bed for what was then the Union Pacific railroad on the west. Highway 195 finished the property’s frame on the south.

When you stand on the property and look east across the creek, your field of vision is filled with a tall wall of sandy dirt rising steeply for about 500 feet. Your eyes are instantly drawn to the top of the bluff upon which sits High Drive and Spokane’s South Hill. Before and after the war, well-to-do Spokanites built spacious homes along High Drive so they could gaze out over the less affluent residents in the green valley below.

Turning to the west, you see a gradual, pine and fir-speckled rise toward the West Plains, home to Spokane International Airport and Fairchild Air Force Base.

The sediment the creek piled here through the millennia has been good to this valley. When Verne was a teenager, the neighborhood was carpeted with orchards, family gardens, and truck farms, which supplied the city’s markets with fruit and vegetables. Today, manufactured housing has replaced much of what had been groves of fruit trees and fields of berries. Most of the orchards are gone but there still are a handful of commercial and community gardens and greenhouses.

Once they purchased the land, Grandpa and Verne spent evenings and weekends scraping and leveling the ground and building a simple two-story house. Emphasis on “simple.” It looked handmade. It was small with no fancy adornment. The exterior was plain wood planking, which Grandpa would later cover with a reddish tar paper siding textured to look like brick.

It must have seemed like Heaven.

Grandpa built the house toward the south end of his property and set it back from the highway enough for a broad driveway. He planned to put a gas station there to take advantage of motorists heading to and from Pullman and the rest of the Palouse. His plan later fell through when the state re-routed the highway. In fact, the state would declare eminent domain in 1960 and force Grandma and Grandpa to sell a large chunk of their property to widen Highway 195 from two to four lanes. Today, motorists traveling in the northbound lanes drive straight through the ghost of the Zornes’ living room.

In late 1941, things were looking up for the Zornes family as they got ready to settle into their modest dream home. Verne was gearing up to graduate from Spokane’s Lewis & Clark High School the following spring. He was learning automotive mechanics through a federal youth Technical and Vocational School program offered through Spokane School District 81. The program was housed less than a mile from Verne’s home at the Lowell Public School, a tan stucco structure which still stands at Inland Empire Way and 22nd Avenue.

Like so many 17-year-old boys, the world must have seemed to offer options limited only by his interests, talents, and gumption.

On December 7, an event three thousand miles away in Hawaii Territory would strip away his choices and narrow his path. It would also change the landscape of our town and the course of our family for generations.